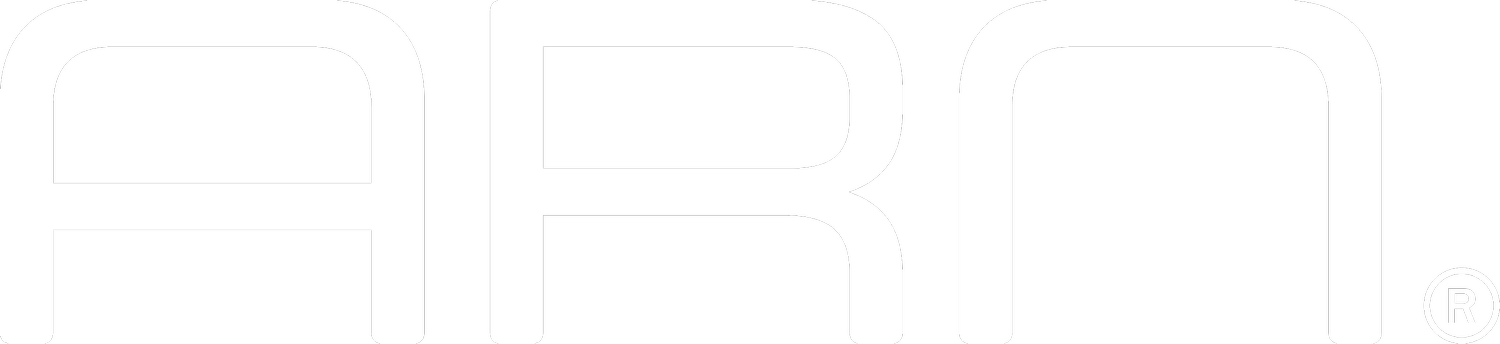

What Happens When Frameworks Meet Lived Conditions

Inclusive frameworks often look strong on paper.

They are coherent, well-researched, ethically grounded, and aligned with global agendas. They speak the language of equity, access, and opportunity. They reference best practices, policy goals, and shared values.

The real test begins when those frameworks leave the document and enter lived conditions.

The GARI project, a global accessibility initiative (led by the Mobile & Wireless Forum), sat precisely at that intersection. My role focused on analysing real-world mobile usage conditions and translating them into structural insights that could inform global standards.

Beyond intention

The work around GARI was not about introducing new ideas.

It was about understanding what happens when good intentions meet:

uneven digital infrastructure

institutional constraints

cultural context

economic pressure

and the realities of people navigating systems that were not designed with them in mind

The challenge was not to argue for inclusion.

It was to make inclusion operable.

That required slowing down and asking harder questions:

Where does this framework break in practice?

Who is expected to carry the cost of complexity?

Which assumptions only hold true in stable environments?

What happens when capacity, connectivity, or continuity cannot be taken for granted?

Designing for friction, not ideals

Much of the work involved translating between layers:

policy language and operational reality

strategy and execution

global ambition and local constraint

This was not about simplifying the problem away.

It was about acknowledging friction as part of the system.

In inclusive work, friction is often treated as failure.

In reality, friction is information.

It tells you where systems are misaligned with the people expected to use them.

Structure as care

What became clear early on is that inclusion does not fail because people don’t care.

It fails because systems are fragile.

Frameworks collapse when they depend on:

perfect handovers

uninterrupted funding

continuous attention

or ideal user behavior

The work required designing structures that could absorb interruption, partial adoption, and uneven participation (without losing coherence).

This meant prioritizing:

clarity over comprehensiveness

adaptability over completeness

durability over elegance

Good structure, in this context, became a form of care.

A recurring pattern

One pattern kept resurfacing throughout the project:

The further a framework travels from where it was designed, the more it reveals what it actually depends on.

This is where inclusive work becomes honest.

Not through ambition, but through constraint.

Not through scale, but through stress.

Why this work matters beyond the project

What GARI reinforced for me is something that applies far beyond development projects or inclusion initiatives:

Systems fail quietly when they are designed for ideal conditions.

Whether you are designing:

public programmes

digital platforms

organizational structures

or market strategies

The same principle applies.

If a system cannot survive contact with reality, it is not finished.

Carrying the lesson forward

This way of thinking continues to shape how I approach work today.

I pay close attention to:

where responsibility accumulates

where complexity hides

and where structure silently shifts burden onto people

Because inclusion, at its core, is not a statement.

It is a design challenge.

And design only proves itself when frameworks meet lived conditions.